Dynamic Capital Budgeting

The basic principle of an investment: Money is spent today in order to have more cash returns or less cash outflows in the future. Companies, NGO’s, NPO’s and private investors have to decide again and again whether they should invest their available money in companies, plants or process improvements. An investment decision requires a plan-calculation, which should show whether the planned cash outflows and cash inflows can achieve a return in line with the market during the expected useful life of the investment.

Usually investments are expenditures for the provision of a service potential that are intended to generate higher cash inflows or reduced expenditures during the planned period of use.

Simple example 1: Contracting out the maintenance of the garden surrounding the plant to an external organization.

Consequences of this decision are: Additional expenditures for the grounds maintenance contract and eliminated expenditures for paying the former in-house gardener.

Complex example 2: Production and sale of a new product group by an existing company.

In example 1, from a financial point of view it is sufficient to compare the balance of the expected payments for the grounds maintenance contract with the personnel costs for the work previously performed internally.

In example 2, additional net sales and thus additional contribution margins are to be achieved with a newly introduced product group. To generate these additional cash returns initial investments in fixed assets will be necessary, the expansion of net revenue will increase receivables and inventories, and more personnel will be required in individual functional areas. These actions will lead to additional cash outflows. It should also be taken into account that both net revenues and cash outflows will be subject to the life cycle of this new product group, i.e. will lead to different net cash flows in each year of the investment project.

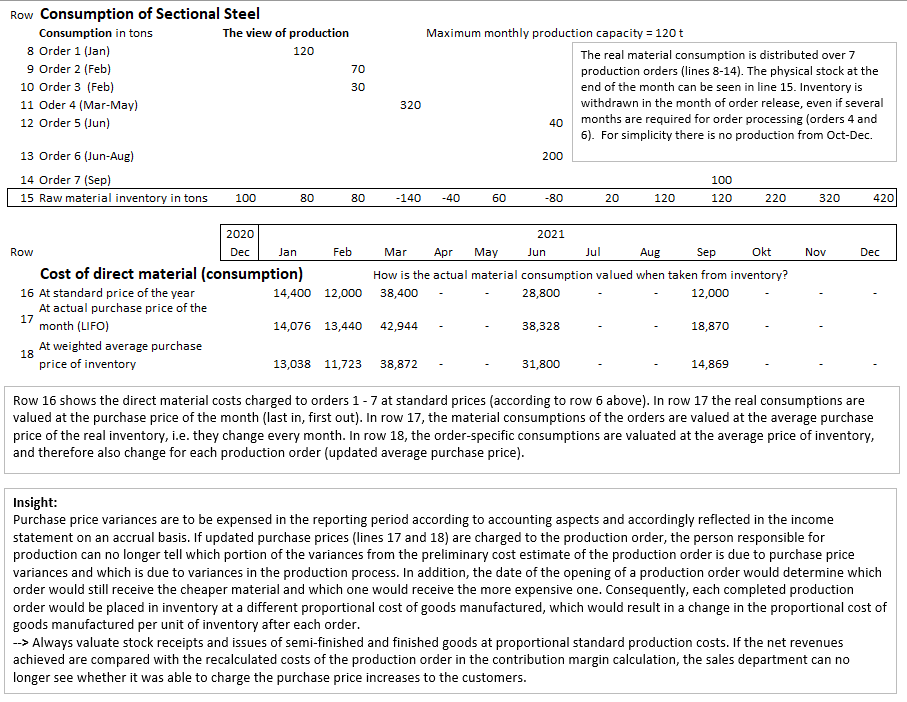

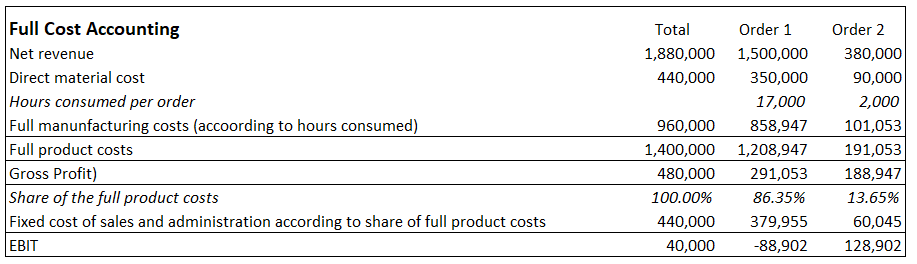

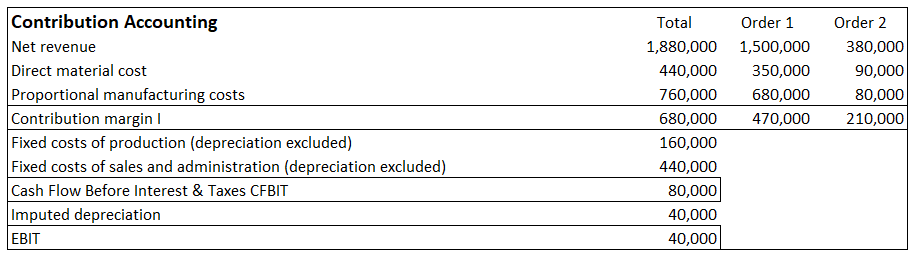

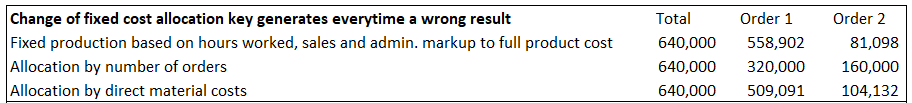

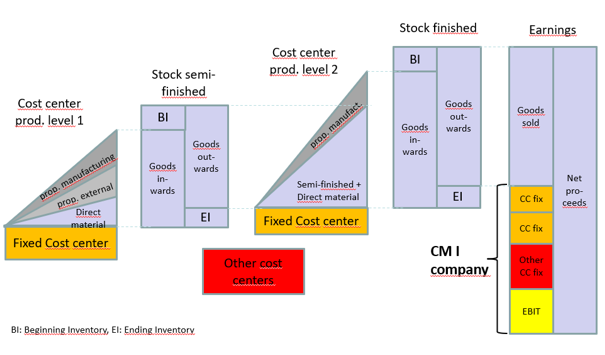

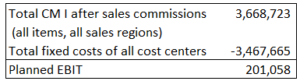

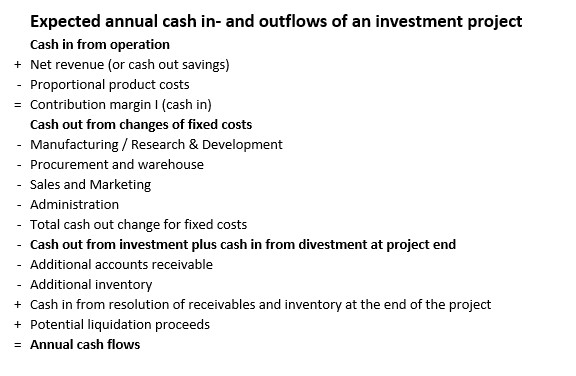

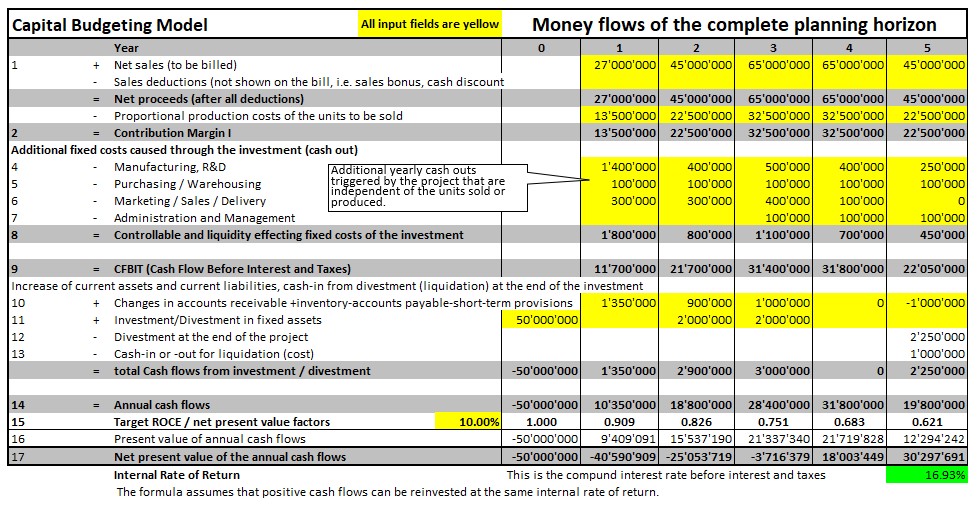

In both cases, cash flow analyses must be prepared for the upcoming decision. For the more complex example of the introduction of a new product group, these considerations must be prepared for a multi-year horizon, because the inflows and outflows of money can occur in different years. In our experience the following structure is suitable for this purpose:

This structure can be used generally for investment appraisals, since it contains all elements of cash inflows and outflows. Regarding example 1, the cash outflows would be the payments for the grounds maintenance contract, the cash inflows would be the saved cash-out personnel costs for the previous employee. The introduction of a new product group (example 2) requires the entry of all items listed in the table above because this investment project affects both the income statement and the balance sheet.

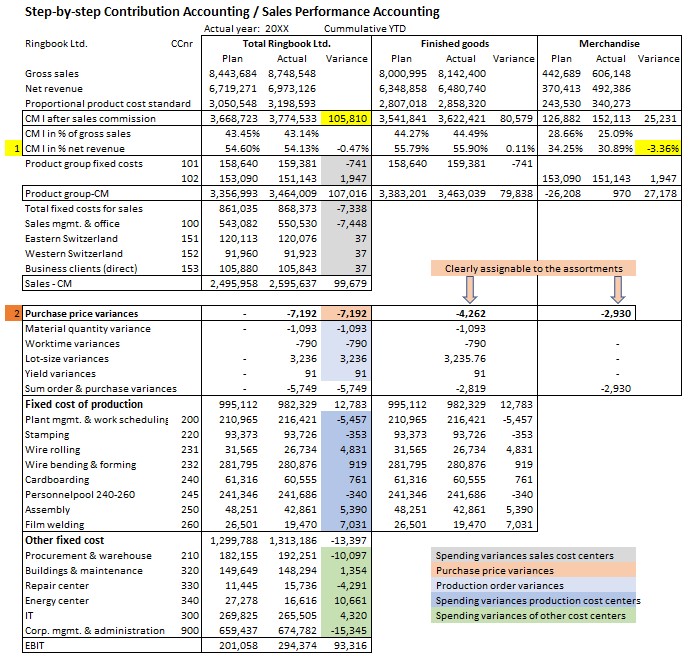

Therefore, it is advisable to prepare the investment appraisal in such a way that the expected annual cash flows can be identified and discounted for each year. In the product launch example, these cash flows are planned as follows:

-

- Year 0 is the beginning of the implementation of the decision. The main investment of 50 million has to be paid then (line 11). For the years 2 and 3 it is assumed that additional investments will be necessary to increase the production capacity of the plant.

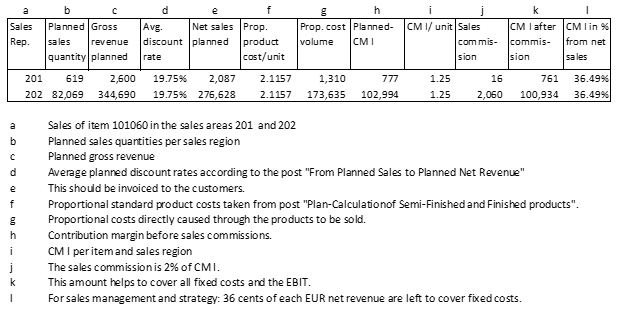

- The annual net revenues expected from the project are entered in line 1. The development of the net revenue corresponds to the expected life cycle of the new product.

- In line 2, the planned proportional costs of the expected yearly sales are calculated (50%).

- In year 1, further payments of 1.0 million are incurred for introductory work. In addition, it is expected that the staff in Production Planning and Control will need to be increased, resulting in 0.4 million additional annual expenditure (line 4).

- Further additional personnel are required in the areas of purchasing and warehousing as well as marketing / sales / distribution. The expansion of the business volume will also require an additional person in administration in the years 3-5 (lines 5-7).

- The total annual cash outs for internal tasks of this project (additional personnel) can be seen in line 8).

- Line 9 shows the net benefit of the investment project (yearly net cash inflows).

- Lines 10 and 11 show the net impact of the project on fixed assets, accounts receivable and current liabilities over the years.

- At the end of the project (here year 5), the built-up receivables and inventories are liquidated again. There may also be liquidation proceeds for the asset that is no longer in use (lines 10, 12 and 13).

- The annual balance of cash flows is shown in line 14.

- The example shows 5 plan years but can be extended for more years as needed.

Adding up the nominal yearly net cash flows in line 14, it can be seen that the investments will be completely paid back during year 3 (simple payback period).

The time value of money

Anyone who provides money, whether it is the company itself or an investor, expects to be remunerated for this service in the form of interest. If, for example, an annual interest rate of 10% corresponds to current money market conditions, a company must pay an interest of 100 for a loan of 1,000 at the end of a year. If the lender is to make the money available for several years (example 2), he will ask himself whether he will be remunerated for his investment with compound interest. Consequently, from his point of view he wants to know at the time of decision what the present value of the investment will be over the entire term of the loan and whether this return will stand up in comparison to other possible investments.

Investors therefore ask themselves: How much will I get back for my investment at the end of one year or at the end of the project? If, as in the example, he sets a target interest rate of 10% per annum, the result is:

Interest for 1,000 investment amount = 10% * 1,000 = 100 p.a.

The 100 are to be paid at the end of the year. So the value of the interest payment at the beginning of the year, respectively at the time of the decision for the investment is 90.9091 ((100 : (1+interest rate 10%) = 90.91).

If the interest of 100 accrues only at the end of year 2, the 90.91 must be divided again by the interest rate (90.91 / (1+interest rate)) = 0.826). In the compound interest calculation, the formula 1 / interest rate ^number of years is used. This results in the present value factors, which are shown in line 15 for the rate of 10%. The corresponding present values of the plan years are shown in line 16. Line 17 shows that the accumulated present values will only at the beginning of year 4 be sufficient to pay for all the investments and divestments and for the 10% compound interest (lines 10 and 11) at 10%.

Overall, according to the plan, by the end of year 5, the cumulative present values in example 2 should be 30.298 million higher than the net investments in all the years of the project. In setting up the example, it was assumed that the life cycle curve of the product group will go through its build-up and growth phase in years 1-2, will reach saturation in years 3 and 4 and that the phasing-out of the life-cycle will begin in year 5.

Pitfalls in the application of Dynamic Capital Budgeting

-

- Depreciation has no place in an investment calculation. This is because by taking the investment amounts into account the cash outflows are already included.

- Likewise, tax consequences of investments are generally not included, since the profitability rate to be achieved refers to the profit before deduction of interest and taxes.

- Saveable tax amounts are also not relevant to the decision because taxes are calculated from the reported profit after interest. The latter can also develop negatively if an investment project is going well but the market situation leads to a drop in sales of other products and thus to less annual profit.

- As the name implies, capital budgeting is a forward-looking view. The method is always based on planned quantities and values because it is intended to support decision-making in strategic and operational planning. Whether the investment has really increased productivity can only be determined by evaluating the actual data from management accounting.

With the present-value approach the investment appraisal becomes dynamic.

Download the Excel model for the quantification of investment projects here and adapt it to your own needs. Copying the formulas in new rows allows to include additional years. The model is particularly suitable for the quantification of strategies. With the help of the Excel formula “Internal rate of return” also the internal rate of return of the project can be calculated (see the 16.9% on the right in line 18). This helps to compare competing projects. But it should be noted that this formula assumes that cash returns can also be reinvested at the rate of 16.9%.

Market rate of interest

In the presented example an interest rate of 10% was assumed. But which interest rate should be applied for the assessment of a real project plan or a general investment?

For this purpose, the interest rate in line with the market for companies with the same risk must be determined. The procedure for doing this is described in the post “Profit in Line with the Market“. There, it is also noted that the 10% assumed in the example above correspond to the market reality in German speaking countries and in the US.