Activity Based Costing (ABC)

ABC was published for the first time 1971 by Professor George Staubus under the title “Activity Costing and Input Output Accounting”. CIMA, the Chartered Institute of Management Accounting, designated ABC in 1988 as a cost accounting method, which assigns the costs of resources consumed to the final products. This allocation is to be achieved with the help of consumption estimates and cost drivers:

Resources -> cost drivers -> cost objects.

The purpose of these allocations is to estimate or determine the full costs of products, services and performed work. Thus, ABC is a further attempt to assign, if possible, all costs of an enterprise properly to the individual unit sold. Activity Based Costing was, in 1999, so up-to-date that Horngren/Bhimani/Foster/Datar dedicated a whole chapter to the topic in their book “Management and Cost Accounting” (pp. 344-370). This development was taken up also in the German speaking countries. Peter Horváth extended ABC to Process Cost Calculation (P. Horváth, Controlling, 7th edition, 1998, p. 532 ff.,). “The Process Cost Calculation is to be understood as a method to allocate overhead costs to products according to the German account system for external reporting (ibid. p. 533, translated by L. Rieder)”.

In ABC as well as in Process Cost Calculation the fixed costs of manufacturing, selling and administration are allocated to other cost centers and from there to the different product units (see ibid., p. 542). The intention is to be able to better assess the profitability of a product or service and to enable “fact-based pricing”.

In the following it is examined how far ABC can lead to more decision-relevant cost information and which internal inventory evaluations are decision-relevant.

Cost Elements in Activity Based Costing

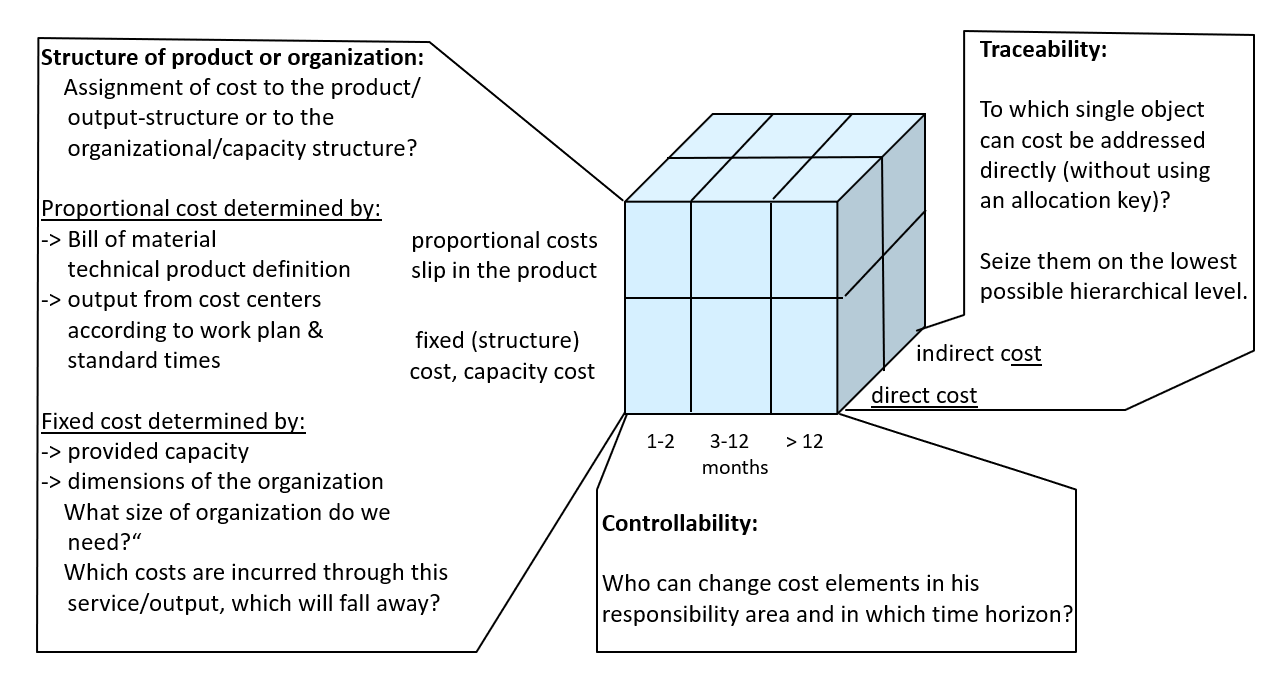

In the cited book “Management and Cost Accounting” (p. 345 ff.), three guidelines for determining activity costs are defined:

-

- Account for all costs either as direct costs of a product or a cost center. If direct allocation to a cost center is not possible, the cost items are to be charged to a higher aggregated cost center. In the cost cube (see below), these are the direct costs of the respective cost center under consideration (Traceability).

- Refine the cost center structure so that each cost element can be assigned to one and only one cost center. While this leads to a massive increase in the number of cost centers to be planned and tracked, it also leads to clear responsibilities for the cost center managers.

- Define a cost key for each cost center that represents a direct cause-and-effect relationship between a cost center’s activity and its costs. This requirement leads to the allocation of fixed costs from one cost center to another and from there to the products. It thus contradicts the requirements for cause-related cost splitting between proportional and fixed.

From a management perspective the guidelines 1 an 2 can be agreed upon. However, guideline 3 contradicts the rules of flexible budget costing, as it leads to fixed costs also being allocated to manufactured items and services.

The cost cube (compare the post “Management-relevant cost terms”) shows that the proportional costs are caused directly by the quantity of a product or service produced (direct cause-and-effect relationship). The fixed costs, on the other hand, are the result of decisions by the cost center manager and his superiors.

The most important parts of these fixed costs are the personnel costs for the management of the cost center and the costs for the calendar-dependent depreciation of the plant. They are created so that the cost center is ready to perform, even if production is not taking place. All fixed costs are period-dependent, not piece-dependent and can therefore not be attributed to a manufactured unit in accordance with the cause.

If the total cost center costs of a period were divided by the cost center services provided by that period, a different full cost rate would result for each month. This would be useless for the management of a cost center as well as for the inventory valuation of semi-finished and finished products and would cause variances for which no one is responsible.

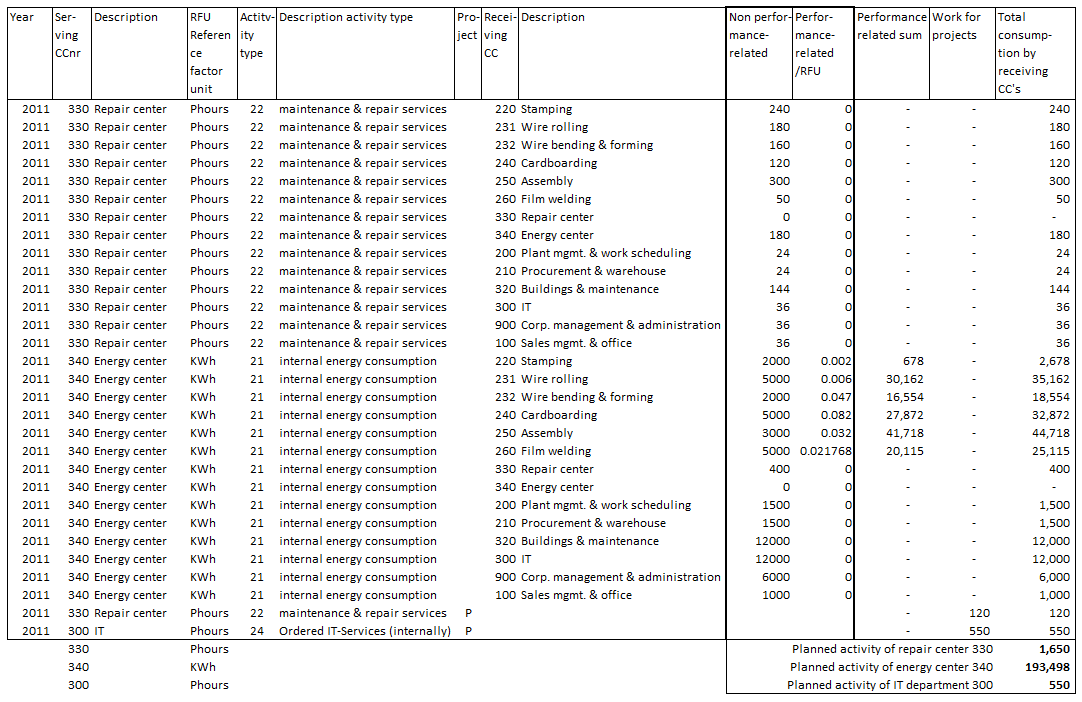

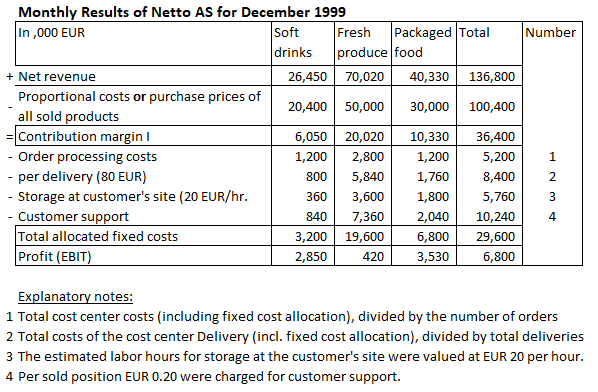

ABC is thus also to be understood as full cost calculation. For each cost center an activity unit, called a cost driver, is specified, which measures the demand of the resources. All costs of a cost center are then divided by the number of performed activity units. The resulting cost rate thus consists of proportional and fixed cost portions. This is indicated in the following example for the food wholesaler Netto AS (translated from “Management and Cost Accounting, pp. 350 – 352).

Activity Based Costing at Netto AS

Since Netto AS is a trading company, which itself does not change the products it purchases, the difference between net revenue and proportional purchase costs of the sold products results is contribution margin I.

For the allocation of the cost center costs to the product areas of Netto AS, however, the conventional full cost method was used. For this purpose, the total costs of a cost center including allocations from supplying cost centers (e.g., energy, personnel administration or corporate management) were divided by the presumed characteristic activity quantity of the cost center. For example, the cost center “Customer Support” recorded total costs of 10,240 in 1999 and processed 51,200 order items with them. This results in a fixed cost rate of 0.20 EUR per order item, again including all allocations from other cost centers. This rate is multiplied by the number of order position of a product range, which results in the amount of 7,360 for fresh products.

Taking all these cost allocations into account, the result is that Fresh Produce contributed “only” 420 to EBIT in 1999. One could conclude from this that the sale of fresh products could be abandoned and the time gained in the cost centers could be used for the more profitable product areas or the personnel could be reduced to a corresponding extent.

A look at the contribution margin line reveals that this would probably be short-sighted. This is because fresh product sales generate 20,020 contribution margin I, i.e., more than half of the total CM I of 36,400. The lost 20,020 CM I would have to be saved in fixed costs, which would primarily mean personnel layoffs. The risk is great that in this case there would also be a lack of qualified personnel to carry out the sales and delivery activities for the other product ranges. In addition, the storage areas would become too large and the installations no longer in use, including computers and software, would still have to be depreciated. The fixed costs of the central functions of Netto AS, e.g., management, IT or personnel administration are already included in the sales processes in the numerical example (numbers 1-4). These would not be reduced by discontinuing the Fresh Produce range, as they are necessary for Netto AS to be able to perform. As a consequence, the other product areas would have to bear higher allocations, which in turn would reduce their profitability.

These considerations show that activity-based costing can be used to calculate the estimated full costs of an activity. But these full costs cannot be relevant for decision-making if fixed costs are allocated to product or customer groups by means of an allocation key. In Flexible Standard Costing, proportional costs are allocated to product units according to their source. The fixed cost center costs are transferred however as blocks into the contribution margin calculation.

The ABC idea is consistent with GPK (Grenzplankostenrechung) and RCA (Resource Consumption Accounting), to the extent it assigns proportional costs to products. But it also allocates fixed costs without appropriate cause-and-effect allocation keys (or cost drivers). This application of other allocation keys does not reduce the fixed costs and can lead to erroneous decision making based on misleading costing information. As with any costing method, care must be taken when using ABC costing data to ensure the information used is appropriate for the decision being made.