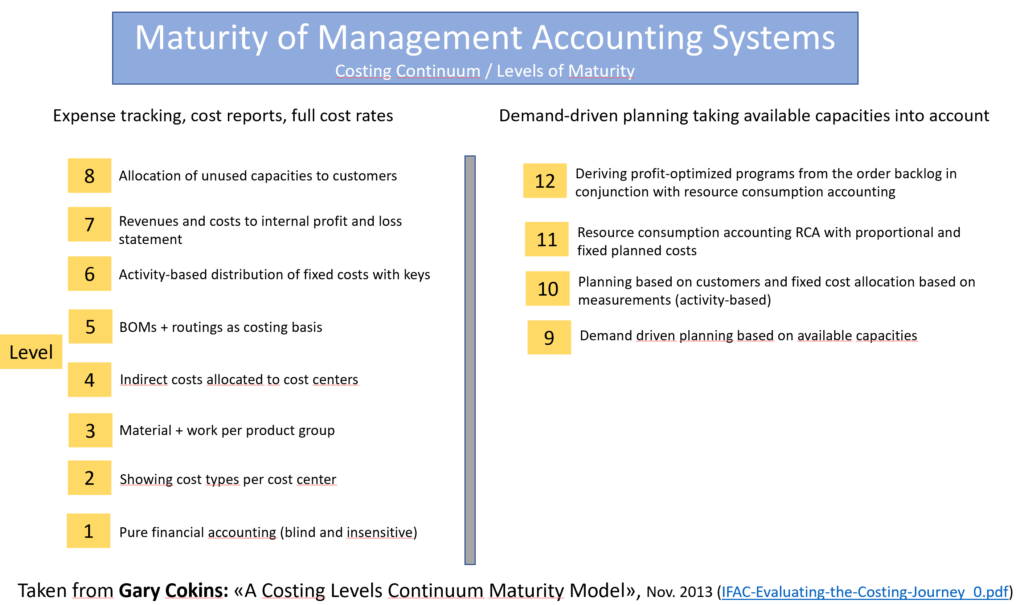

Maturity Level of Your Management Accounting

Gary Cokins from North Carolina, USA, developed the “Costing Levels Continuum Maturity Framework 2.0”. Its version 2.0 was reviewed by the International Federation of Accountants IFAC in 2013 and published as a guide to good practice in cost accounting (IFAC-Evaluating-the-Costing-Journey_0.pdf).

This framework is designed to help management accounting professionals assess the maturity of their own system. How well does the system work in providing managers with data that is relevant to their decisions and their responsibilities?

It also helps organizations align the maturity level of their management accounting system with the decision-making needs of their managers.

12 maturity levels of your own management accounting

Cokins structures the Costing Levels Continuum Maturity Model into 12 maturity levels, ranging from simple accounting analysis to a comprehensive simulation model:

-

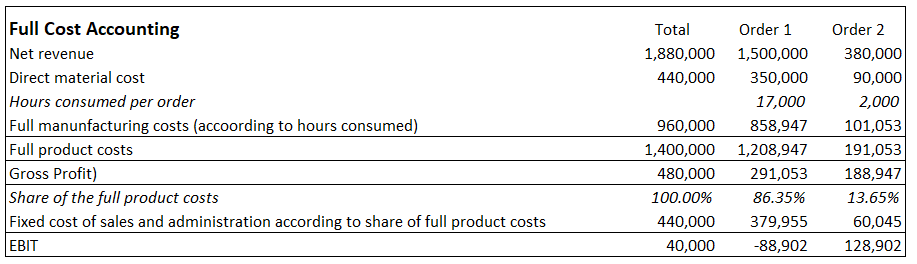

- Levels 1-8 cover the systematics from financial accounting to internal accounting, activity-based full-cost accounting (also known as standard full-cost accounting), cost allocation using activity-based costing (ABC), the comparison of revenues and costs per customer, and the quantification of unused capacities.

- Levels 9 and 10 compare plan to actual comparisons and attempt to allocate fixed costs to products and customers based on activities.

- Level 11 requires the implementation of Resource Consumption Accounting (RCA). RCA corresponds almost completely to Grenzplankostenrechnung according to H. G. Plaut, Flexible Budgeting according to W. Kilger and the multi-level and multi-dimensional Contribution Accounting as described in this blog.

- Level 12 is reached when simulations from the product and customer level to the entire company are possible on the basis of level 11 data.

Description of the 12 levels

-

- Level 1 is pure financial accounting (general ledger, payroll accounting, purchasing)

- Level 2 also assigns the expenses to cost centers and cost types

- Level 3 posts the direct material and labor costs per product group (also fixed labor costs)

- Level 4 allocates the indirect costs of the service areas to the cost centers that work directly on the products with the help of a single allocation factor.

- Level 5 looks at individual manufactured units for the first time. This requires links to bills of materials and the work schedules (ERP). The manufactured quantities are generated from historical data. In expanded versions, the costs are also recorded per production order or per project.

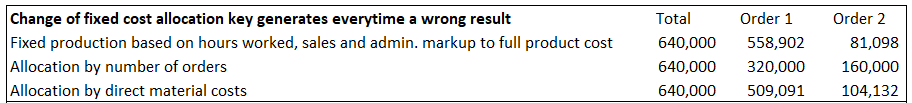

- Level 6 attempts to allocate fixed costs to individual products on the basis of estimated or measured consumption using Activity Based Costing (ABC) (this still corresponds to an unfair allocation of fixed costs).

- Level 7 includes sales and net revenues for the first time. It attempts to allocate the costs of marketing, sales and promotion, as well as the entire administration and management, to customers and products using allocation keys. These allocations are shown in the period statement for each customer or product but are not included in the inventory values.

- Level 8 calculates the costs of unused capacities (personnel, machinery, IT, other equipment) of the cost centers and attempts to allocate these to the customers and sales channels.

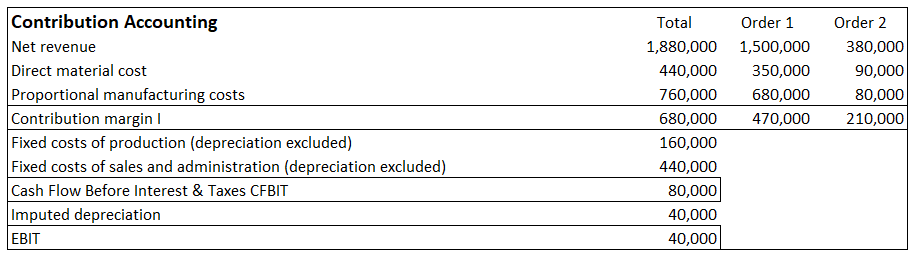

- From level 9 onwards, planned and actual values for revenues and costs are used to support decision-making and thus planning. This brings the splitting of costs into their proportional and fixed portions to the fore. In addition, planning is based on the needs of existing and potential customers, rather than just on the people and equipment available.

- Level 10 only uses planned quantities and times derived from target-oriented planning to calculate products. These form the standards. However, fixed costs continue to be allocated to products and customers via the cost rates of the cost centers.

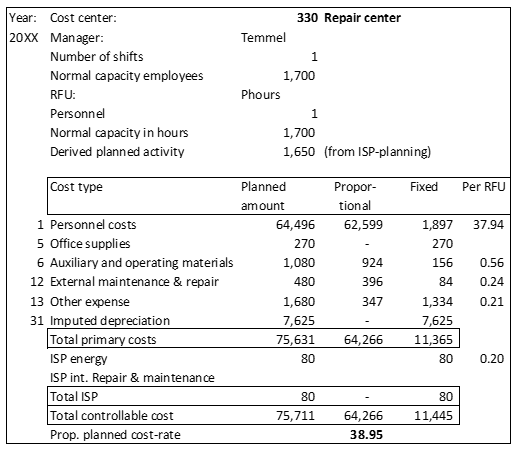

- Level 11 brings the comprehensive application of the causation principle as described in this blog and being used since many years in Grenzplankostenrechnung (GPK) and Flexible Budgeting in German-speaking countries. These two systems are largely consistent in terms of methodology. In the US this method is known as Resource Consumption Accounting (RCA). RCA also wants to answer the question: How much should the produced or sold products and services have cost, if they had been provided exactly according to plan?

- Level 12 is reached when simulations can be run based on level 11 (GPK or RCA) and on the ERP and CRM data. The aim of simulations is to determine and implement programs that optimize results on the basis of current order backlogs and management accounting data.

Background and purpose of the continuum

The Costing Continuum Model was developed based on knowledge of the application of different cost accounting systems in the English-speaking world, particularly in the United States. The model is indirectly a consequence of the famous book by Robert Kaplan and Thomas Johnson entitled “Relevance lost. The rise and fall of management accounting” (Harvard Business School Press, 1987). This book also criticized the fact that most cost accounting departments focus on meeting reporting standards (US GAAP / IFRS) but that hardly any suitable systems are used to support managers’ decision-making. From 2004, it was recognized that Marginal Cost Accounting (Grenzplankostenrechnung GPK) and Flexible Budgeting can largely cover these needs. In the USA, this led to Resource Consumption Accounting (RCA, level 11).

In German-speaking countries the software developments by the Plaut group and SAP, as well as many other software providers, led to many companies that reached level 11 in their management accounting. However, in our practical experience, compliance with accounting standards and statutory accounting and transfer pricing regulations still takes precedence over decision support for managers at all levels and in all functions.

The Continuum is designed to help controllers and finance professionals assess the extent to which the systems and processes they have installed provide relevant information for management decision-making. This applies to both operational and strategic management.

Application of the Maturity Model

Organizations using Flexible Budgeting or GPK are at level 11. For this they need to have access to ERP-data as well as sales and revenue planning and to link those to Management Accounting. This is a prerequisite to reach levels 11 and 12. For running simulations quantities and services must be available as planned and actual figures for each item number and customer and for each cost center. Flexible Budgeting is to be set up in the cost centers so that the actual costs can be compared with the planned costs of the services provided.

Even if artificial intelligence is used to plan and control success, it derives its suggestions from the available plans and the actual data. It cannot develop new plans.

In the simulation model of our book “Management Control System”, it is possible to change prices, sales deductions, quantities, services and proportional cost rates. The Excel-model immediately calculates the consequences of changes in the basic input variables through to the internal profit and loss statement and the internal balance sheet.

This is not artificial intelligence, but it allows decision-makers to follow the consequences of each change step by step.