Management accounting has decision relevance when it can quantify objectives in plans, compare the results achieved with the plans, document the differences that arised and offer leverage points for improvement. In addition, it should provide support for the assessment of forecasts.

10 Principles for Decision Relevance

Implementing this uncompromising management orientation in the design of the management accounting system requires application of the following principles:

1 Work with standards:

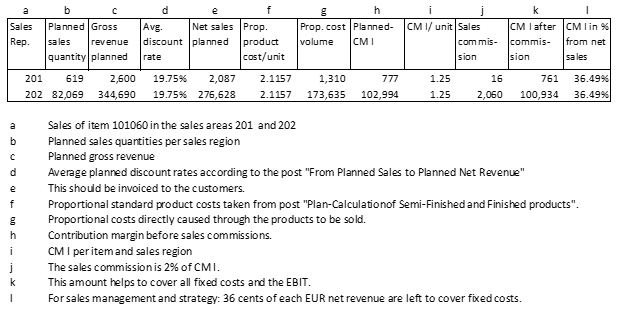

Management means goal-oriented proceeding. This requires that all objectives be transformed into a measurable format. As far as management accounting is concerned this requirement can be met with a standard costing system. It can be applied to prices, services, cost and revenues. Standards and the standard cost system are not new. They are often described in literature and installed in practice (see Horngren, et al., 1999, p. 575 ff.).

New is the importance these methods gain in a management-oriented design of a planning and control system. A planned purchase price for a raw material determines for the plan year the expected average purchase price to be paid for raw material or supplies. For the responsible purchaser, this value is the yardstick against which he can measure the achievement of his price objectives. By displaying purchase price variances, procurement can see how well it succeeded in realizing the target prices.

For the users of an item (for example, production), the internal standard purchase price remains unchanged during the whole year. This equally applies for merchandise in the sales organization.

2 Plan and record direct costs:

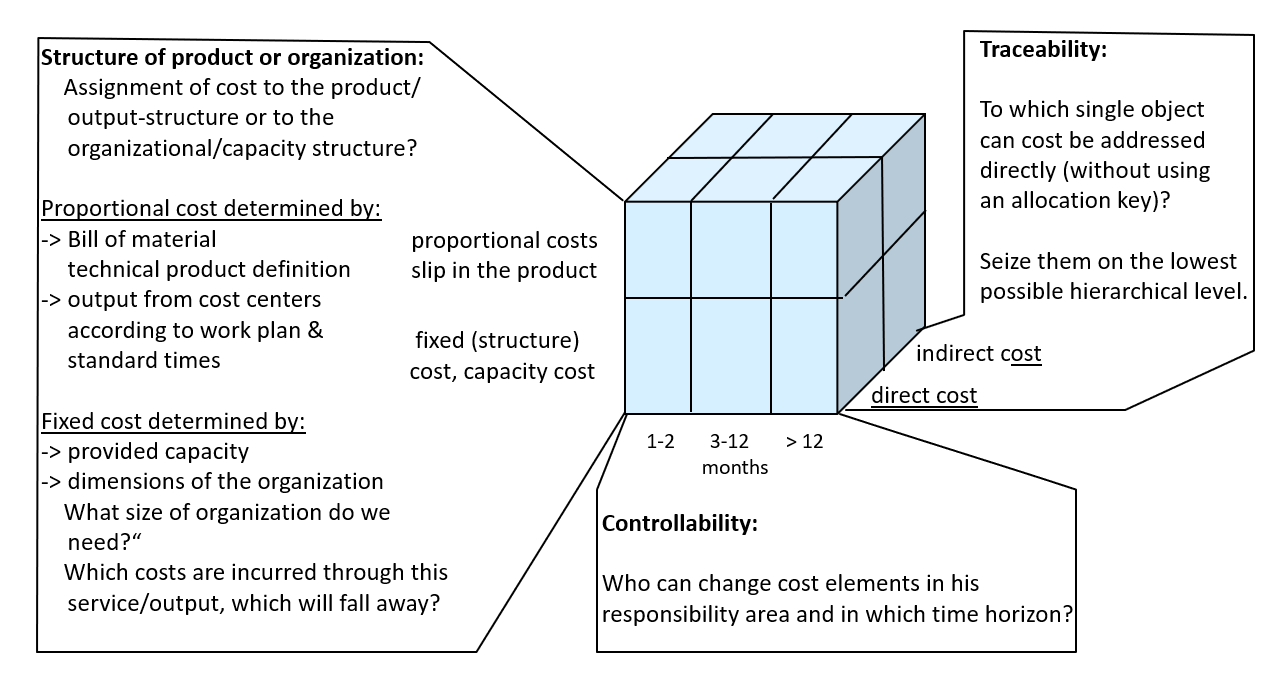

A manager will rightly insist that his area of responsibility only be charged for services, consumption and revenues that he or his employees can influence directly and thus for which he should be held responsible. That includes withdrawals from inventory (raw material, semi-finished and finished goods), external purchases directly for one’s own cost center (area of responsibility), services from other cost centers (if the consumption can be determined directly by the receiver, i.e., real internal activity charging), as well as costs that can be clearly assigned to an item/product.

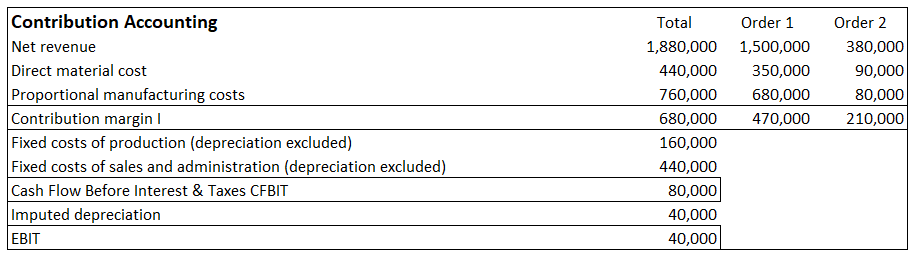

3 Distinguish consistently between proportional and fixed costs:

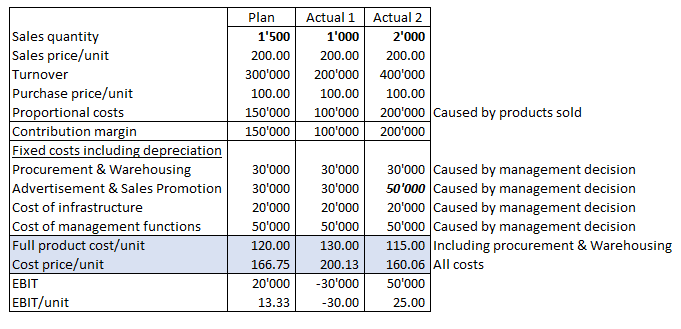

Proportional costs are those costs caused directly by the production of units, as opposed to fixed or structural costs which result from decisions by management concerning capacities or the structure of the organization. Decisions regarding fixed costs are always made by managers. Proportional costs can be clearly compared with the units produced and the sales achieved. Proportional costs are driven by quantity and product structure. Fixed costs are the result of management decisions and are the responsibility of the deciding manager.

4 Plan and record sales deductions according to source:

Bonuses and reimbursements are usually granted retrospectively based on sales achieved in a given period. Whether cash discounts were taken can only be determined after receipt of payment. All sales deduction items should be subtracted monthly from the monthly billings. This has the advantage of not overstating a company’s profits during the year. As the actual amounts of many sales deductions are not yet known at the reporting date, standard rates should be applied and deducted from sales. These standard rates should thus be used in preparing the monthly reports.

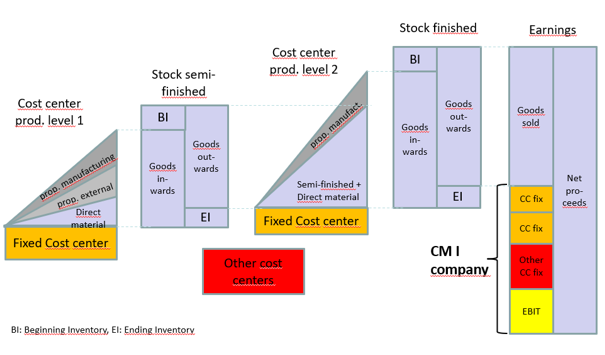

5 Always valuate stock receipts and issues with proportional standard costs:

Similar to the valuation of raw material issued to production at the planned purchase price, standard rates (based on proportional costs) should also be applied to the valuation of receipts to and issues from the semi-finished or finished goods warehouse as well as to the valuation of goods in production, WIP. This means that all production activities performed on production orders are always valued at proportional standard cost (proportional planned cost rate of the respective performing cost center). Additions to the semi-finished goods warehouse are valued at the planned proportional product cost, as are withdrawals of finished products for sale.

This principle results from the management orientation. If in a cost center the actual costs deviate from plan, the cost center manager is charged with taking corrective action so that the variances disappear in future reporting periods. He must ensure that these deviations are rectified by means of corrective measures. Recipients of his services, be they a person responsible for production orders or a cost center manager who receives internal services, cannot directly influence these variances. From a management point of view, it is appropriate that variances are always reported at the point of origin and not passed on to the purchasing or consuming units. They are only to be presented in the overall result of the operating unit. In any case, the allocation of variances to subsequent cost centers or to products is inappropriate as there is no direct causal link between the cause of the deviation and the actions of the recipients.

6 Present contribution margins after deducting proportional standard product costs:

The planned and the realized revenues (gross and net) should always be compared to the proportional standard cost of goods sold. Production managers and their cost center managers are responsible for variances on the manufacturing side; sales is responsible for the realized net revenues.

7 Revalue year-end inventories:

The application of the standard system for the calculation of proportional standard costs requires that, in the transition from the old to the new year, all inventories must be valued with the planned proportional unit cost for the new year. If, for example, an item becomes more expensive in the new year due to price increases in purchasing or due to higher proportional cost rates (e.g., higher wages), the inventories available at the end of the year are to be revalued with the new standard rates. This prevents “comparing apples to oranges” in the planned year.

This revaluation at year end is to be implemented without affecting net income. The assessment of net income for the current year is based on the standard rates for the current year, while the assessment for the following year is based on the new rate.

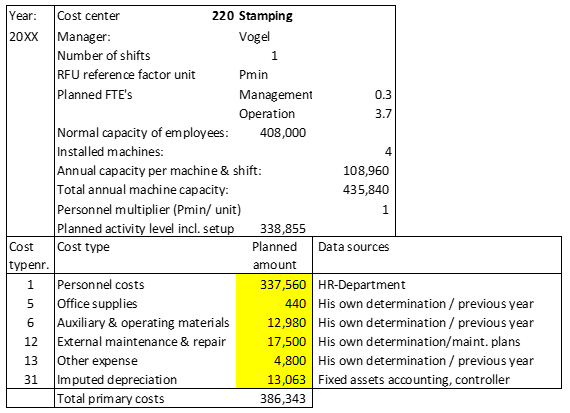

8 Value fixed assets at replacement value and use imputed depreciation:

It is advisable to value fixed assets at replacement value. This gives the responsible managers a more realistic feeling about the investment needed to produce and sell their products. Replacement value is estimated with the question: “How much would have to be paid today if the asset in question were bought and installed newly and what is the planned useful life of this new asset? From these specifications, one can calculate imputed depreciation for each asset and therefore also for each cost center.

Imputed depreciation is a fair guess of the cost of use of the currently invested assets and should be deducted whenpresenting the internal EBIT to management. The total of all replacement values minus the cumulated imputed depreciation roughly shows management the necessary net investment in fixed assets to run the business.

9 Do not allocate fixed costs:

Fixed cost should neither be passed on from one cost center to another nor allocated to manufactured or sold items. The amount of fixed costs is determined by the decisions of the respective cost center manager and his superiors. They are therefore responsible for these amounts.

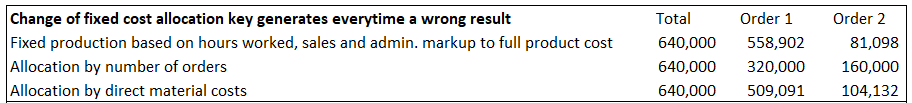

Since there is no direct “cause-effect-relationship” between fixed cost and units produced and sold, any allocation of fixed cost to other cost centers and from there to product units is not appropriate.

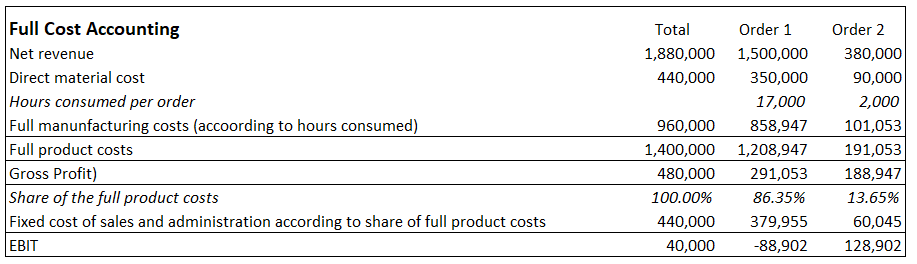

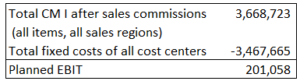

The so-called “as realistic as possible causal relationship” does not actually exist. It can only be constructed with an arbitrary allocation basis. Because of this, neither full manufacturing costs nor cost-prices per unit should be calculated in accounting for management. Fixed costs are passed on as cost blocks in the step-by-step contribution margin accounting.

10 Include in reports only revenue and cost figures that can be directly influenced by a manager:

A manager should only be held responsible for what he can directly influence himself. All plans and reports about revenues and cost should be presented in a performance-related way so that the addressee recognizes the connection immediately. Items that cannot be influenced (e.g., allocations) are not to be shown. Input services from other areas should always be valued at proportional standard rates, as the influence is exerted through the service provider. Additionally, the receiver of the report should be able to derive the time-period in which he can change individual items from the report.

Insofar as external reporting requirements, local tax law, or the determination of transfer prices require the disclosure of full manufacturing costs, these calculations should be performed outside the management accounting system. External financial statements should only be shown to those managers who bear (co-)responsibility for these so that the different valuation approaches do not create confusion within the company.

Overall, the decision- and responsibility-oriented design of the management accounting system should always be structured in a way that each manager can immediately recognize for his area which items he is directly responsible for and thus has to react to if actual results do not proceed according to plan and requires corrective measures.

While these 10 principles contradict in many ways those used in common accounting practice, they are essential for developing and implementing effective management control systems. Most ERP-systems can be rearranged to reflect this management orientation without requiring a change of software.